What if Clive Barker had a fever dream of Snow White as imagined by Angela Carter? This is the question nobody but me asked, but I imagine Angelin Preljocaj’s Blanche Neige to answer.

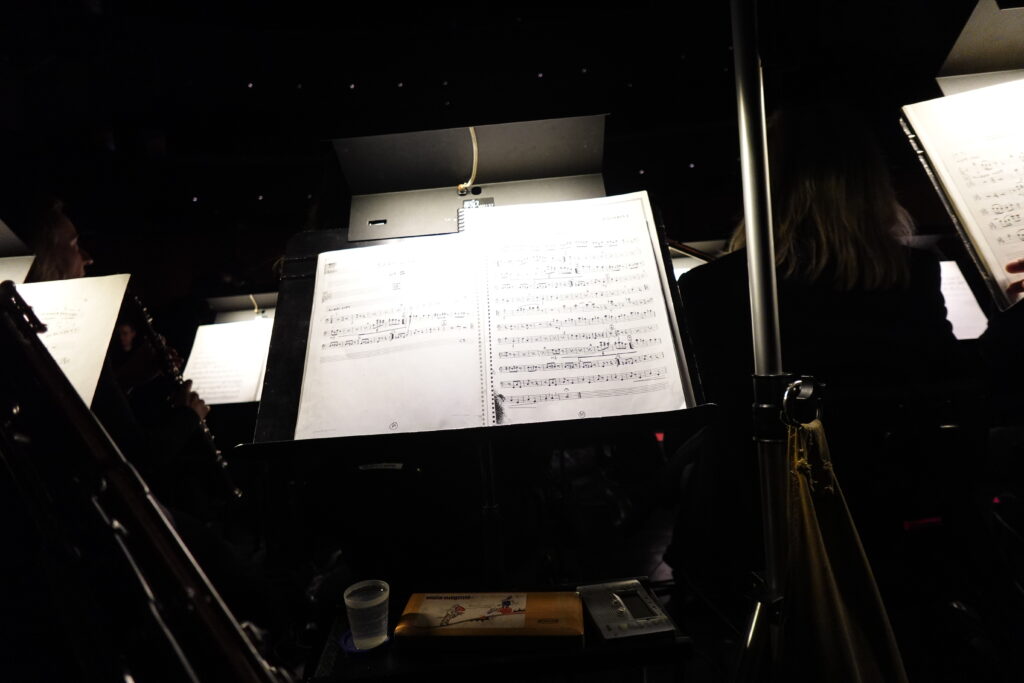

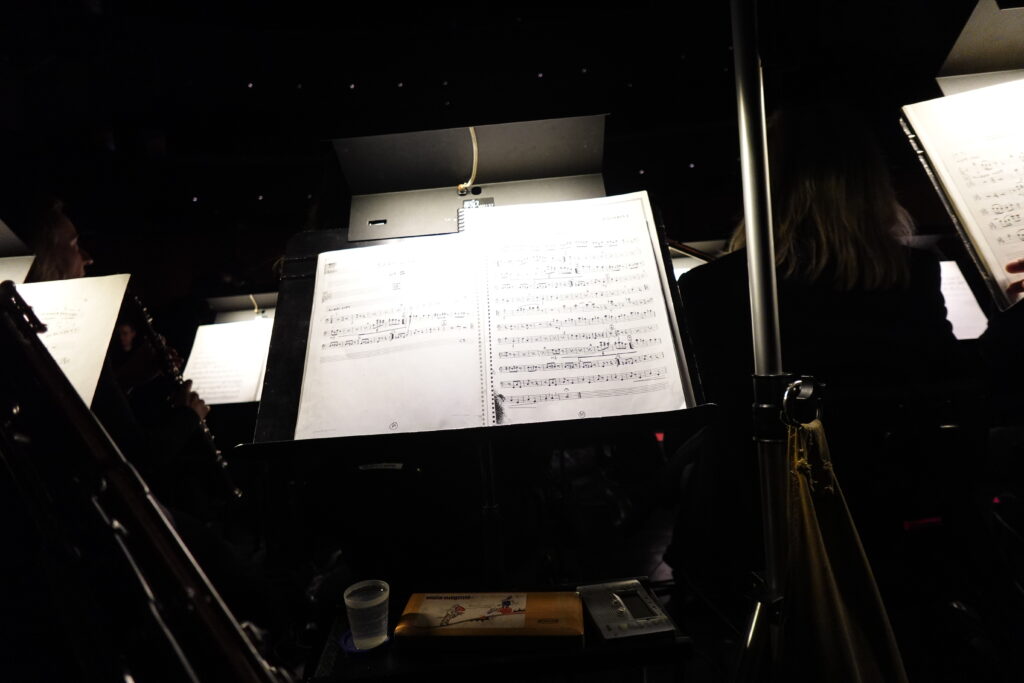

Winnipeg is one of my favourite orchestras to play with, and recently I was invited to play guest principal for the Royal Winnipeg Ballet’s production of this show. The draw for musicians is that it’s a new ballet constructed entirely out of Mahler symphonies; but once I watched a video of a previous production sent to the orchestra, I was also excited for the reaction to the work, which is– look, I don’t think it’s particularly controversial to say that this is a very sexy ballet. The costumes were designed by Jean Paul Gaultier. The sexy cats had headgear intended to convey the danceable impression of ball gags. When Snow White eats the apple, it’s less a trick and more of an orgasmic force feeding.

I’m not casting aspersions. It all– in my opinion, from the production I did watch and the reaction of the Winnipeg audience– worked great. There is something about the project of presenting Mahler as anything other than an integral whole symphony that invites, nearly demands, a certain amount of enjoyable grotesquerie; Ken Russell comes to mind. That said, the music was not as chopped up as you might think it would have to be; no crazy cuts and very few significant alterations to make the music fit the dance. There were even two entire movements, the Purgatorio of the Tenth symphony and the third movement of the First, which accompanied probably one of the most memorable stagings in the show: the introduction of the seven dwarves (I think credited here instead as “miners”), an entire vertical ballet taking place on a sheer rock face, one of the pieces of it that is available online:

The only really wacky alteration was this section, from the very end of the 3rd movement of the Third symphony, being repeated eleven times:

…which is how I learned that in the Brothers Grimm version of the story, the happily ever after is that the Prince orders the evil Queen to dance herself to death while wearing a pair of red-hot iron shoes, which is what is happening during the above. Disney sure didn’t mention that part!

Anyway, I’m very much hoping that the National Ballet or some other company around these parts picks this up, as I’d like to see it properly!

The last time I was at the National Music Camp, I was 14 and played a bassoon for the first time in the beginning bassoon elective. This summer I returned as a faculty member. (Full disclosure… once I started playing bassoon in earnest, my allegiance was firmly to the other music camp, on the grounds that the dining hall was quieter and they didn’t make you do “evening program,” so I never actually attended as a camper on bassoon.)

I didn’t take all that many pictures– one of the excellent things this camp did was take away all the camper’s phones, so there just wasn’t much photo-taking culture in the absence of ubiquitous devices. To be honest, I suspect a lot of the kids (those who didn’t sneak them in anyway, that is) were relieved to have them gone for a week. Hey, maybe they’ll do the same for the faculty in the future!

Laurel leading a very cozy band sectional

A bat taking a rest outside the bassoon studio (I realize this does not exactly look like the peak of bat health, but at least it flew away and we didn’t have a dead bat to deal with…)

Not a camper any more… they can’t force me to stay in the loud horrible dining hall… ate all my meals on the dock with my buddy Montaigne.

Very good doggo getting ready to listen to faculty wind quintet rehearsal

Arcady Ensemble’s “Garden Walk” concert– the first half was a setup where, instead of musicians assembling in a central location for a concert, musicians are spread out through the Whistling Gardens playing solo works with related thematic material, and the audience walks around through them. Ronald Beckett’s music is always fantastic and the dedication of his audience to the ensemble is impressive.

My spot in the garden

The entrance to the performance space

Who am I to disagree?

Project 4 introduced the premise of having “clients” for whom we were tasked with making a product– more or less any product. This seemed to cause wide-scale confusion, since it was not immediately clear what kind of expectation of completeness came along with the introduction of real live human beings who were giving their time and energy to describe their daily lives and health issues to the first-year engineering class. In Project 3, we knew what “success” looked like: if the mechanism dumped the recycling into the bin, we’ve succeeded. The definition of “success” here was somewhat obscure. Was the bare minimum accomplishment supposed to be creating an object ready to be physically given to the clients at the end of the two-month period of the project, with the expectation that they would be able to use it regularly and find it helpful? How useful is the object supposed to be to “count,” especially when compared against the assumed null hypothesis of having one fewer gadgets to keep track of?

Also: what, exactly, would a useful object do? “Problem framing” was supposed to be the focus of the first few weeks of this project, during which the clients, Tim and Kim, came on Zoom to the class lectures; but they didn’t (perhaps had been instructed not to?) actually make any “asks.” Labs for the first few weeks of this process involved mostly group discussions. Unfortunately, the techniques of planning and decision-making that the class was intended to teach, which were required for lab submissions, seemed to actively hinder the process when the goal was so nebulous to begin with. Much has been made during this course of the importance of a “problem statement” that is “solution neutral”; i.e., you want to express the reason for solving a particular problem and the metrics that will tell you whether or not you’ve done so, without committing to, making reference to, or ruling out specific design elements. This makes excellent sense for most professional situations, where a client will come to an engineering firm with a specific thing they need done, made, or improved upon. Solution-neutral problem framing means keeping the big picture in mind and ensuring that the client’s needs aren’t overshadowed by the design process itself.

In this case, however, there seemed to be a lot of confusion about how to generate a “solution-neutral” problem statement without a particularly well-defined problem. Kim and Tim are a couple who both have complex health issues and disabilities. Tim is almost completely blind, and Kim is a power-chair user; there is a large set of problems associated with disability that are simply not solvable, especially not within two months with limited resources of fabrication and, frankly, skill. Many groups seemed to be struggling with the insistence that we state a problem that we were going to solve, without hinting that we had any ideas at all about how to solve it. True solution-neutral problem framing, in this case, would mean committing to solving a problem that you may quickly realize isn’t going to be successfully solved. And there is, of course, an inverse relationship between the significance of a problem and the ease with which it can be solved; the problems of lack of sight, lack of mobility and pain are both the most significant and the ones not likely to be solved in the scope of this project. What’s left, then, is mostly “gadgets” which may or may not end up solving small annoyances.

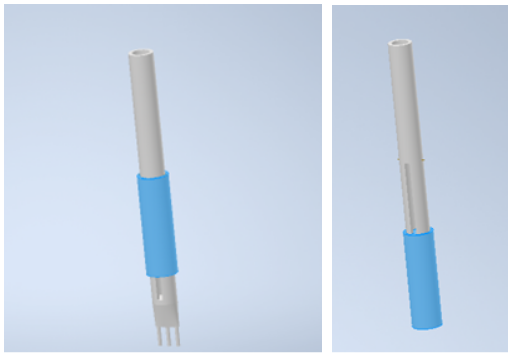

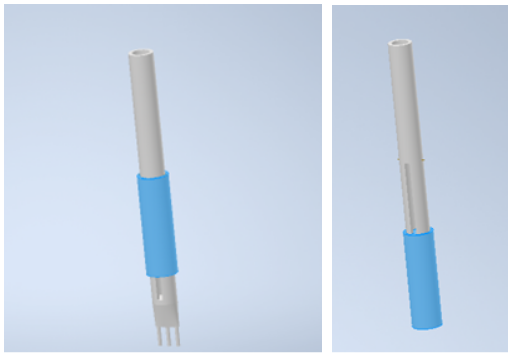

My group had, then, several different concepts for gadgets to choose between, many of which seemed common to many different groups. Tim talked about the challenges of cooking now that he has entirely lost his sight, and kitchen gadgets are a category where it seemed possible to come up with a well-defined problem to solve within the time available, so a quick glance around the 1P13 classroom revealed a veritable warehouse of souped-up utensils. Our three main contenders were an Arduino-controlled device which read out the level of water being poured into a vessel (a device that already exists in a smaller form factor than we would be able to build, and ended up being created by at least one other group for the project), a cutting board with a bunch of Handy™ attachments, which is what we and several other groups ended up doing, and an auto-cutting fork, which I was a little fond of on the grounds that it was at least unique, if somewhat impractical:

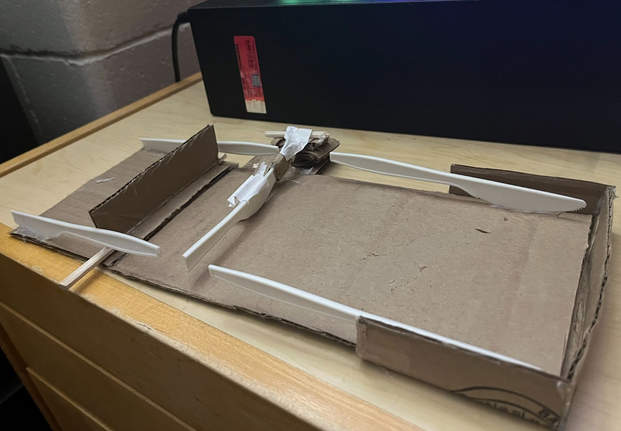

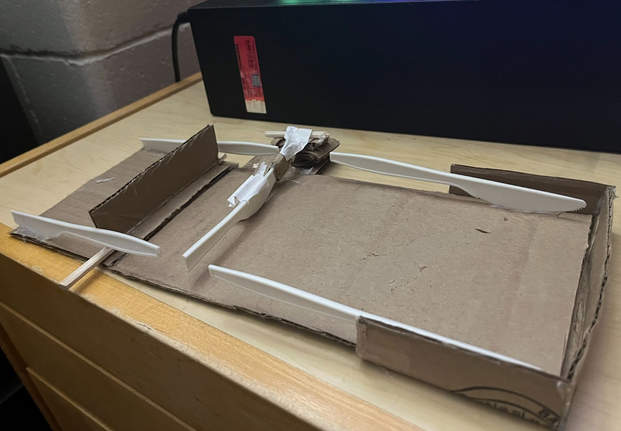

…yeah, it may not look like much, but… OK, there’s no but to that sentence. If we had the ability to fabricate metal, it could have worked– the idea, not exactly clear from a very quick CAD example, would be to have a fork that used a little spring to move a circular wraparound knife up and down; so you can stick the fork into the food, push the knife down to cut a piece of food around the tines, retract the knife (have it held up there or covered somehow so it’s not pointing at your face?), then use it as a fork. As it is, fork tines aren’t a good candidate for 3D printing because they need to get very thin, laser cutting can only cut flat parts along a single plane, and we would have no way of fabricating a circular knife. So, cutting board it was. A groupmate made a cardboard version of the concept, which a) holds the tip of the knife in place, b) has a slide to push food off the board, and c) has a container on the side for the food to be pushed into.

…yeah, it may not look like much, but… OK, there’s no but to that sentence. If we had the ability to fabricate metal, it could have worked– the idea, not exactly clear from a very quick CAD example, would be to have a fork that used a little spring to move a circular wraparound knife up and down; so you can stick the fork into the food, push the knife down to cut a piece of food around the tines, retract the knife (have it held up there or covered somehow so it’s not pointing at your face?), then use it as a fork. As it is, fork tines aren’t a good candidate for 3D printing because they need to get very thin, laser cutting can only cut flat parts along a single plane, and we would have no way of fabricating a circular knife. So, cutting board it was. A groupmate made a cardboard version of the concept, which a) holds the tip of the knife in place, b) has a slide to push food off the board, and c) has a container on the side for the food to be pushed into.

After this, we spent quite a while trying to figure out how to fabricate a better version with the resources available. The two methods of fabrication available through the class are 3D printing and laser cutting of acrylic. Most of the components we needed were long and flat; theoretically candidates for laser cutting, except that they were longer than the sheet of acrylic that each group was supposedly limited to. (Later we learned that the stated limits were more guidelines than actual rules, but that wasn’t officially circulated information.) Of course there are ways to buy all sorts of these materials, such as a knife– but aren’t we supposed to be, you know, making a thing ourselves? What level of “fabrication” was even expected of us? There was supposed to be a $100 limit on materials, but of course rumours swirled– “I heard that group spent $300 on electronic components and clamed they’d had it all lying around the house,” etc– and direct questions about the expected balance between a professional-looking product and a product we actually fabricated ourselves were met with apparent alarm and confusion.

After this, we spent quite a while trying to figure out how to fabricate a better version with the resources available. The two methods of fabrication available through the class are 3D printing and laser cutting of acrylic. Most of the components we needed were long and flat; theoretically candidates for laser cutting, except that they were longer than the sheet of acrylic that each group was supposedly limited to. (Later we learned that the stated limits were more guidelines than actual rules, but that wasn’t officially circulated information.) Of course there are ways to buy all sorts of these materials, such as a knife– but aren’t we supposed to be, you know, making a thing ourselves? What level of “fabrication” was even expected of us? There was supposed to be a $100 limit on materials, but of course rumours swirled– “I heard that group spent $300 on electronic components and clamed they’d had it all lying around the house,” etc– and direct questions about the expected balance between a professional-looking product and a product we actually fabricated ourselves were met with apparent alarm and confusion.

This theoretical speculation was cut short when, one class, a TA informed us that, despite the worksheet’s asking for a “screenshot” of your current prototype, we were actually required to have a new physical prototype built by the next day. So we stopped arguing about how to cut down the 3D printing time on the elaborate knife holder we’d planned. Instead I stopped by Dollarama on my way home from school, bought out their actually pretty extensive craft section, and made this:

If it’s not clear– there are straight razor blades sticking out of that cleaver-looking thing. My groupmates found this very funny when I brought it to class the next session.

If it’s not clear– there are straight razor blades sticking out of that cleaver-looking thing. My groupmates found this very funny when I brought it to class the next session.

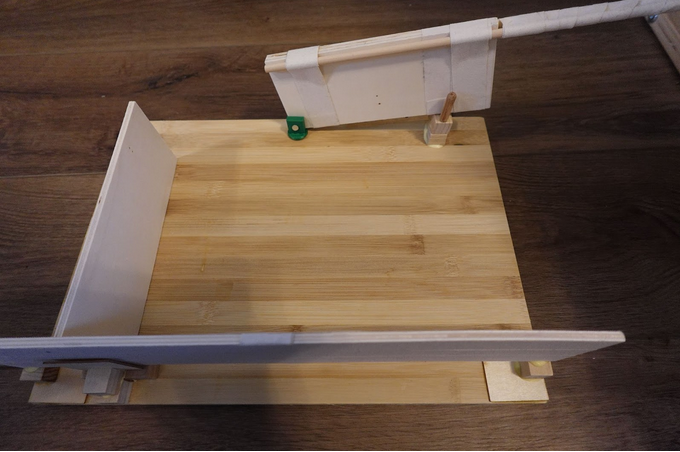

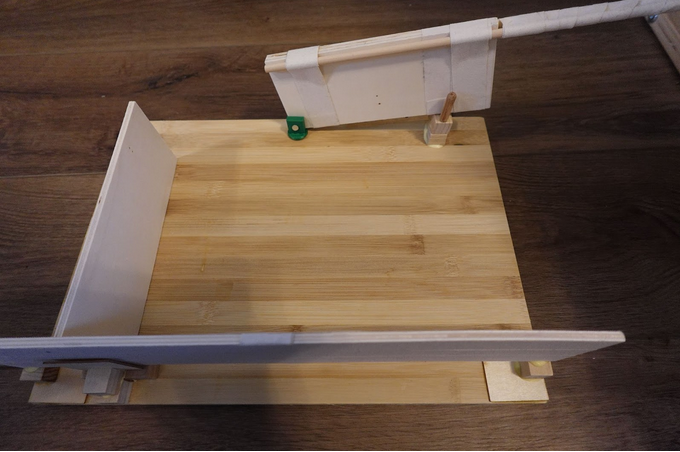

I had assumed that this was just a thing I was building so we’d have something to take a picture of for the submission due the next day; but once it was there, the constraints on fabrication remained, and it wasn’t obvious that we would really be improving it much by replacing wood parts with other materials. Wood is, after all, a perfectly acceptable material for a cutting board as well as many other useful objects, even if “pre-fabricated wood in sizes determined by Dollarama and glued together” isn’t exactly the ideal for high-quality woodworking projects. (I learned during this project that there are woodworking tools available at the Hatch centre; too late to be much use here, since it takes time to get certified to use them, but now that I know that I have all sorts of projects I want to bring there…)

More confusion along the lines of is this, fundamentally, what we are supposed to be doing here? A TA told us the thing basically looked fine as an object to have produced for this project. So my craft project ended up being the final product, with a few modifications– well, actually I had to make the whole thing over just to rearrange the parts a little, because the carpenter’s glue I’d used turned out to work too well. But the final prototype was still Dollarama wood, with a “real” knife instead of my razor-cleaver, and a wooden plate attached to the bottom of the dowel attaching the knife-swivel to the board, so it wouldn’t fall out. There was also a magnetized container added to the side. So, our final product was my first and last cooking vlog.

Project 3 was, in my opinion, the most interesting and useful of the four projects of the 1P13 course, as it consisted of a well-defined problem with clear metrics for evaluating how successful your design was. As in the previous project, the groups of students were divided into “Modelling” and “Computation” sub-teams, which had largely seperate goals, though the overall storyline justifying the assignment had to do with the two sub-teams combining their designs into a single system for sorting recycling.

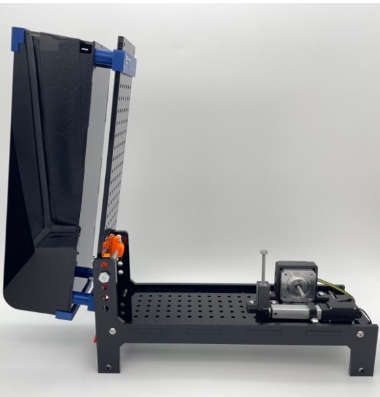

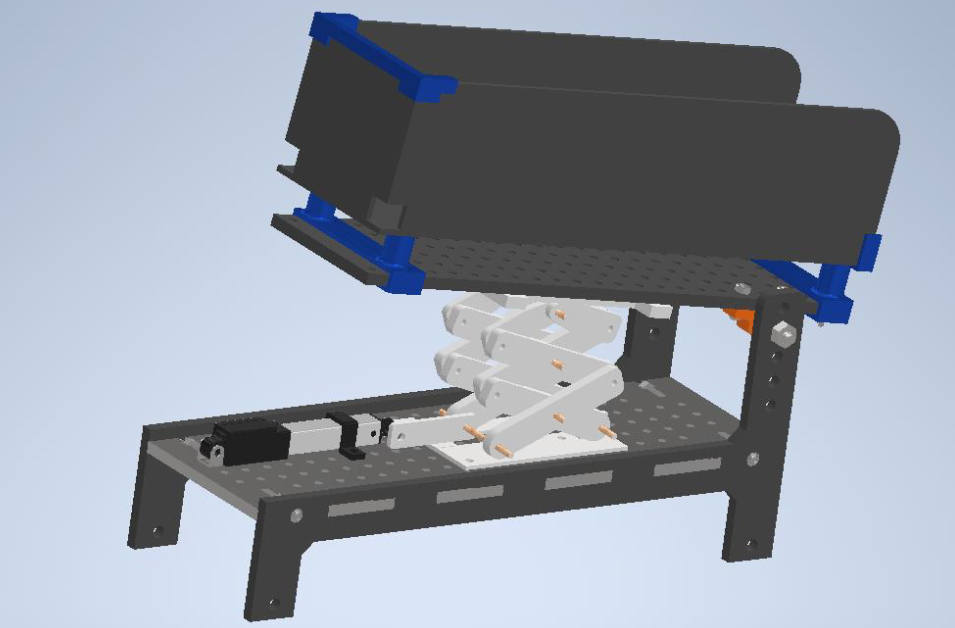

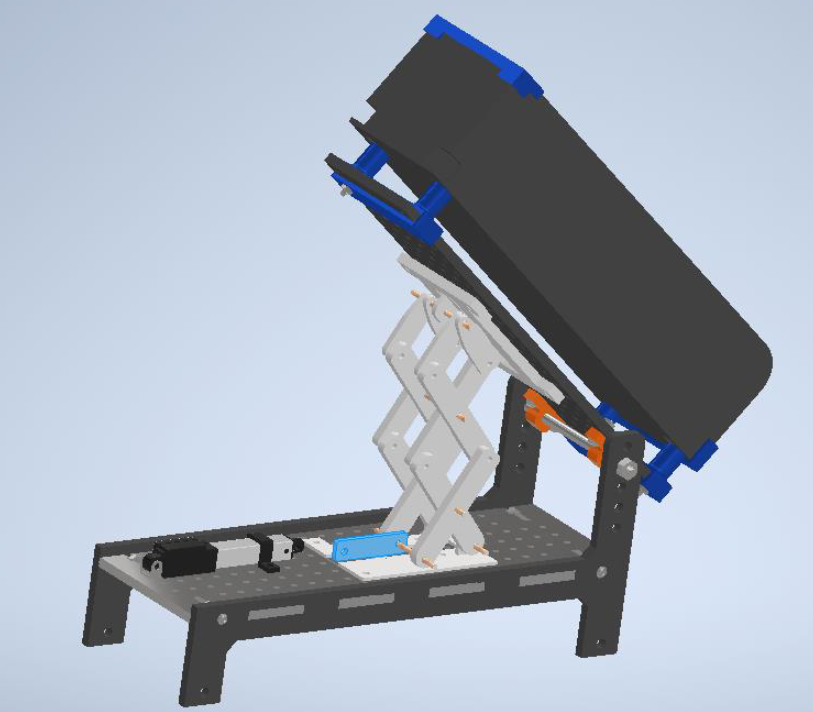

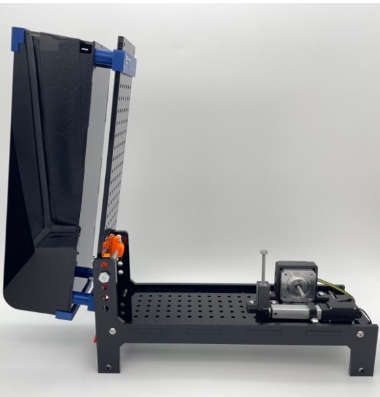

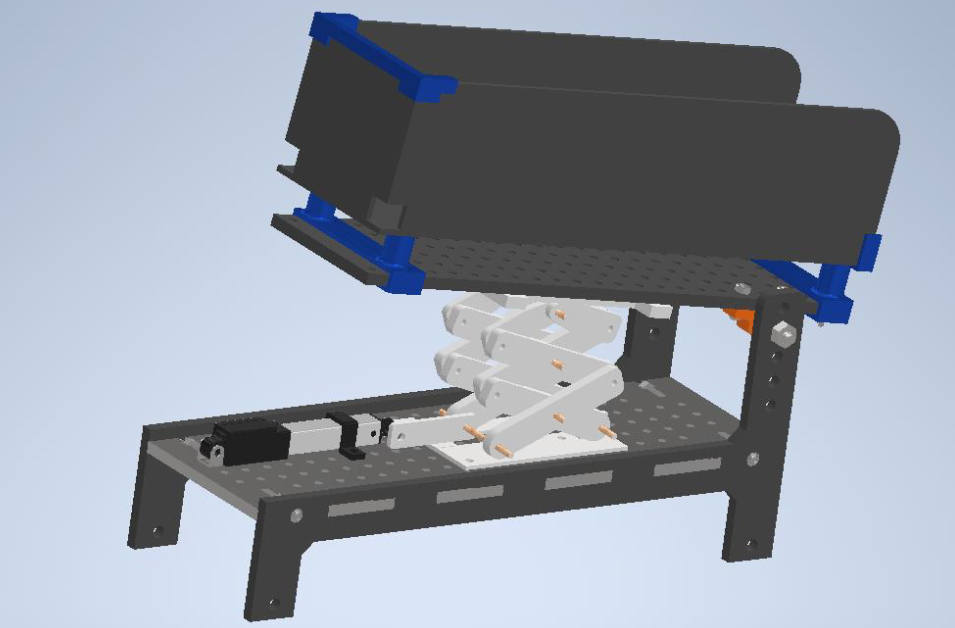

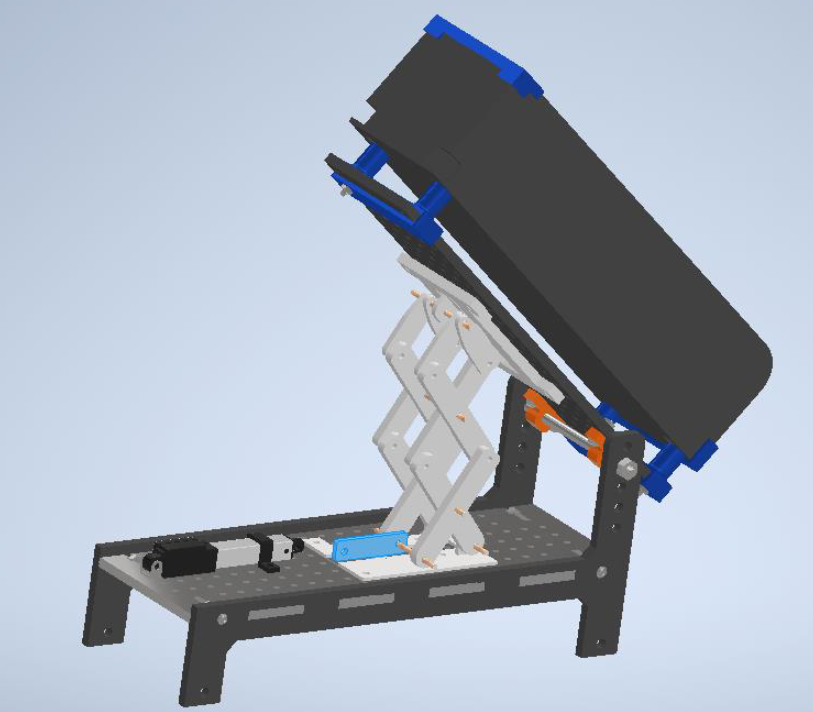

Having done the computing sub-team for project 2, I was on the modelling sub-team for this project. The goal of the physical construction for this project was to design a mechanism that would use either a rotary or linear actuator to raise and lower the container on the upper part of a pre-fabricated hopper, so as to dump out recycled containers contained therein, as in these photos of the starting point provided in the assignment document:

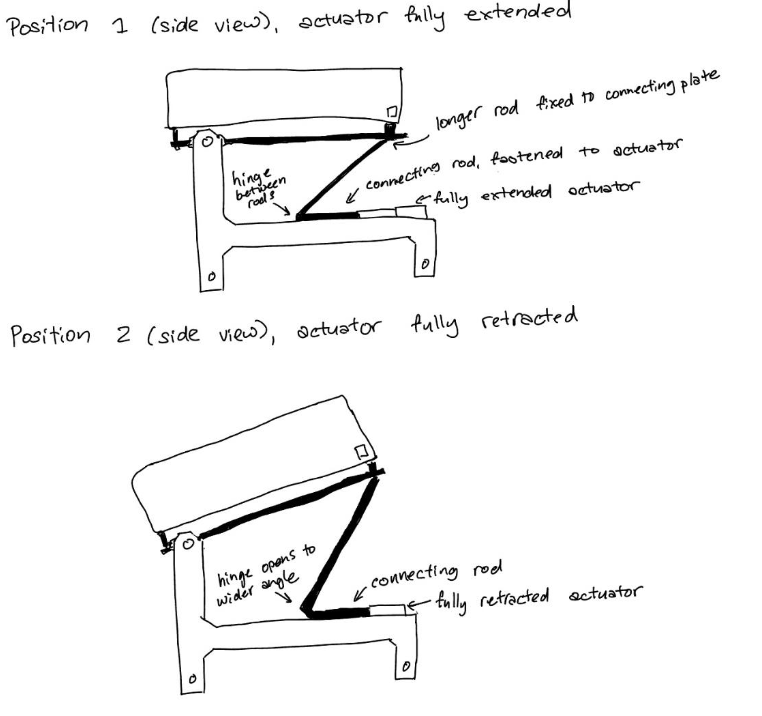

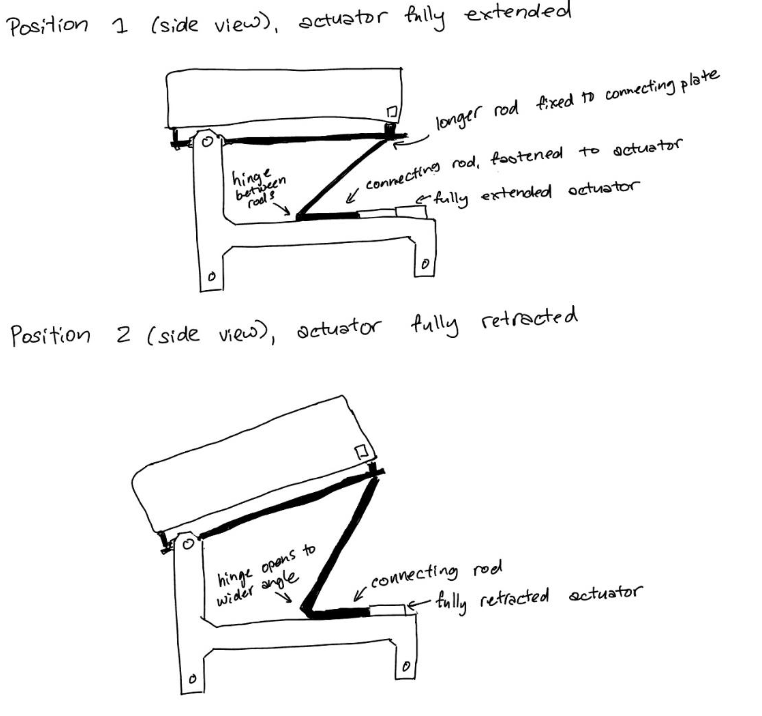

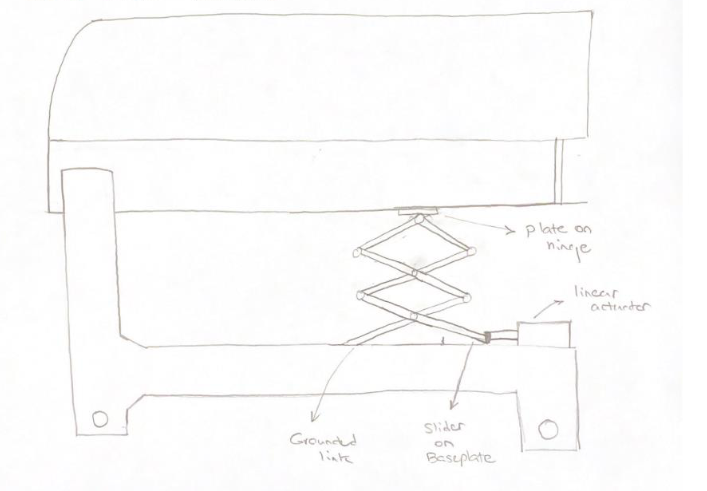

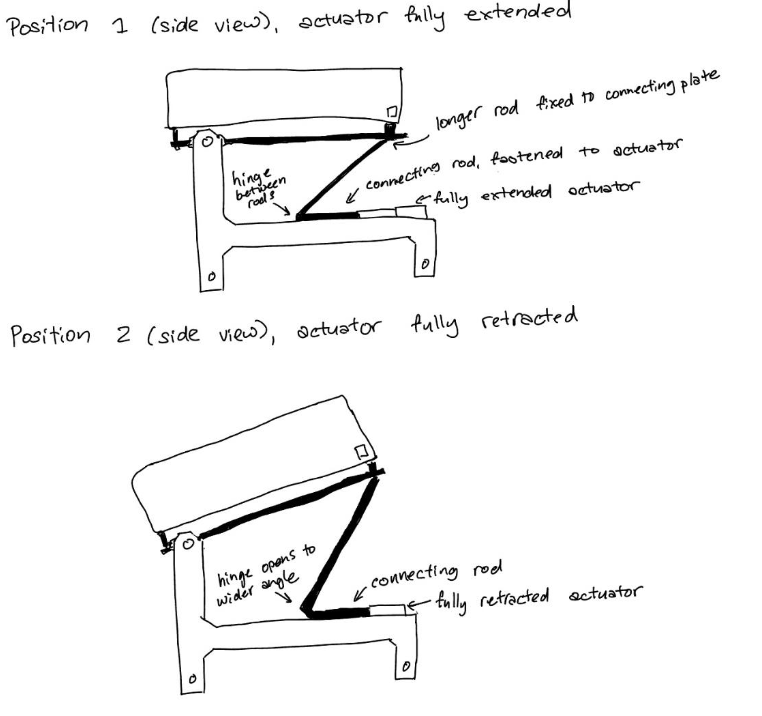

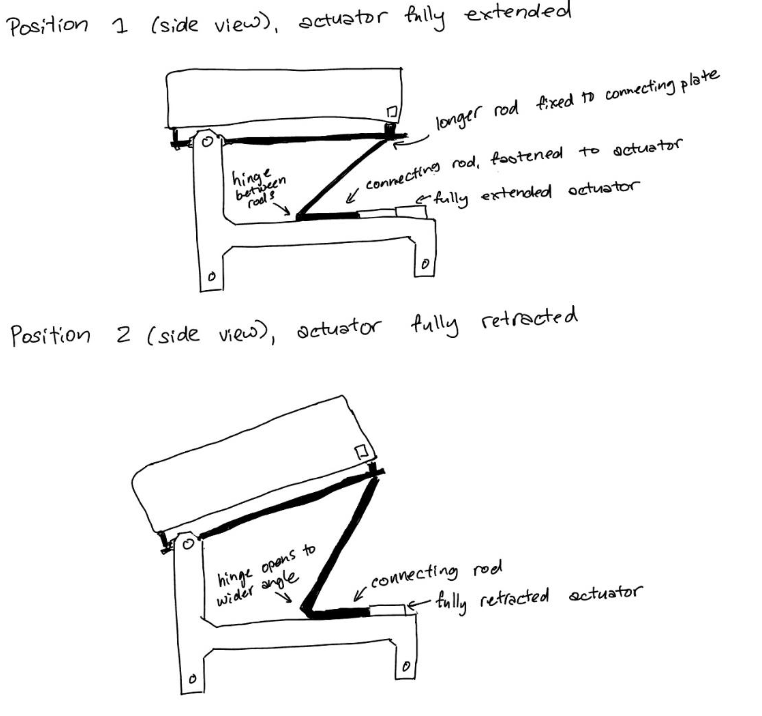

Initially, each member of the group was tasked with coming up with different concepts of how this could be accomplished. My concept for how the linear actuator could be used was pretty much the simplest possible design… a stick. It’s a stick. It raises the top when the linear actuator retracts. Needless to say, I wasn’t exactly jazzed up about the challenges of making this one:

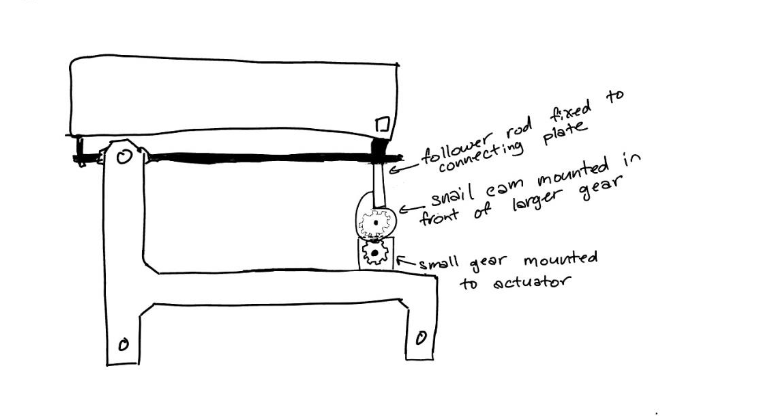

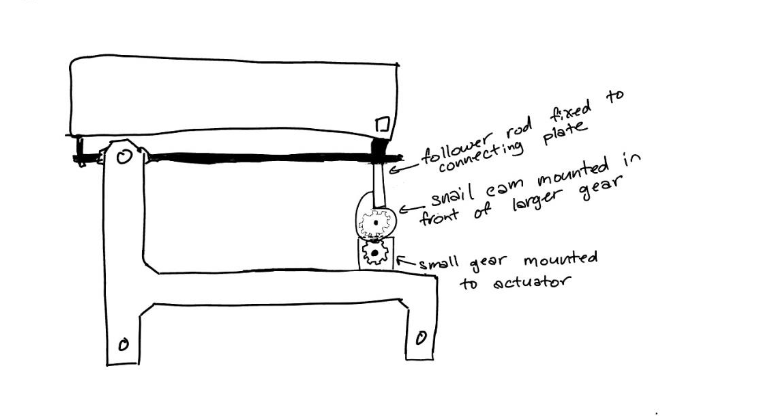

My design for how the rotary actuator could be used was, in my own humble opinion, cooler: it used a set of gears and a cam-and-follower setup to raise and lower the upper platform cyclically as the actuator rotated.

Unfortunately, once we compared this design to the actual size of the hopper our mechanism would need to fit onto, it was clear that the length of cam required to raise the upper platform to a sufficient angle to dump the recycling would not actually fit in the space we had available for the mechanism. actually, all three of us on the modelling team had generated one idea that was cool but impractical, and one that was less visually exciting but more likely to work, all of which were variations on the “it’s a stick, it makes the linear actuator push up” concept.

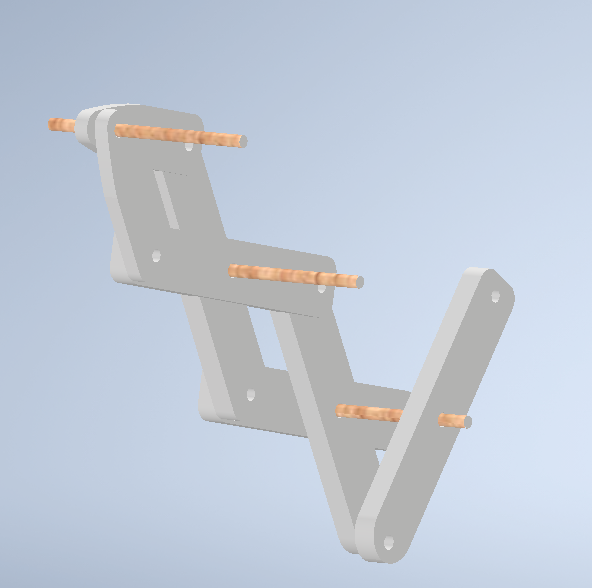

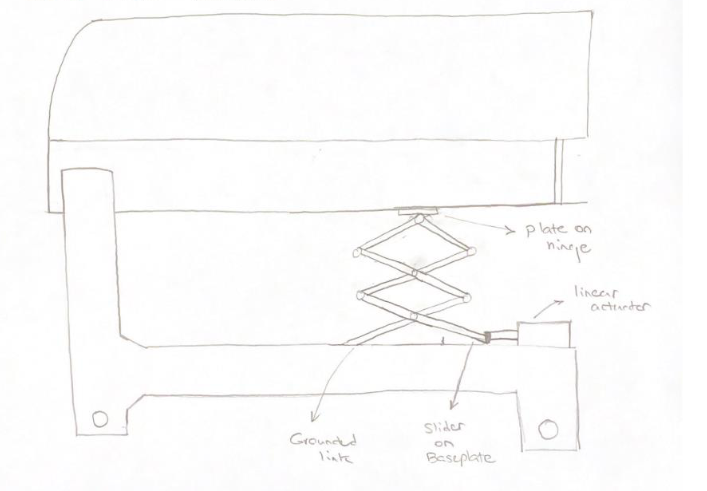

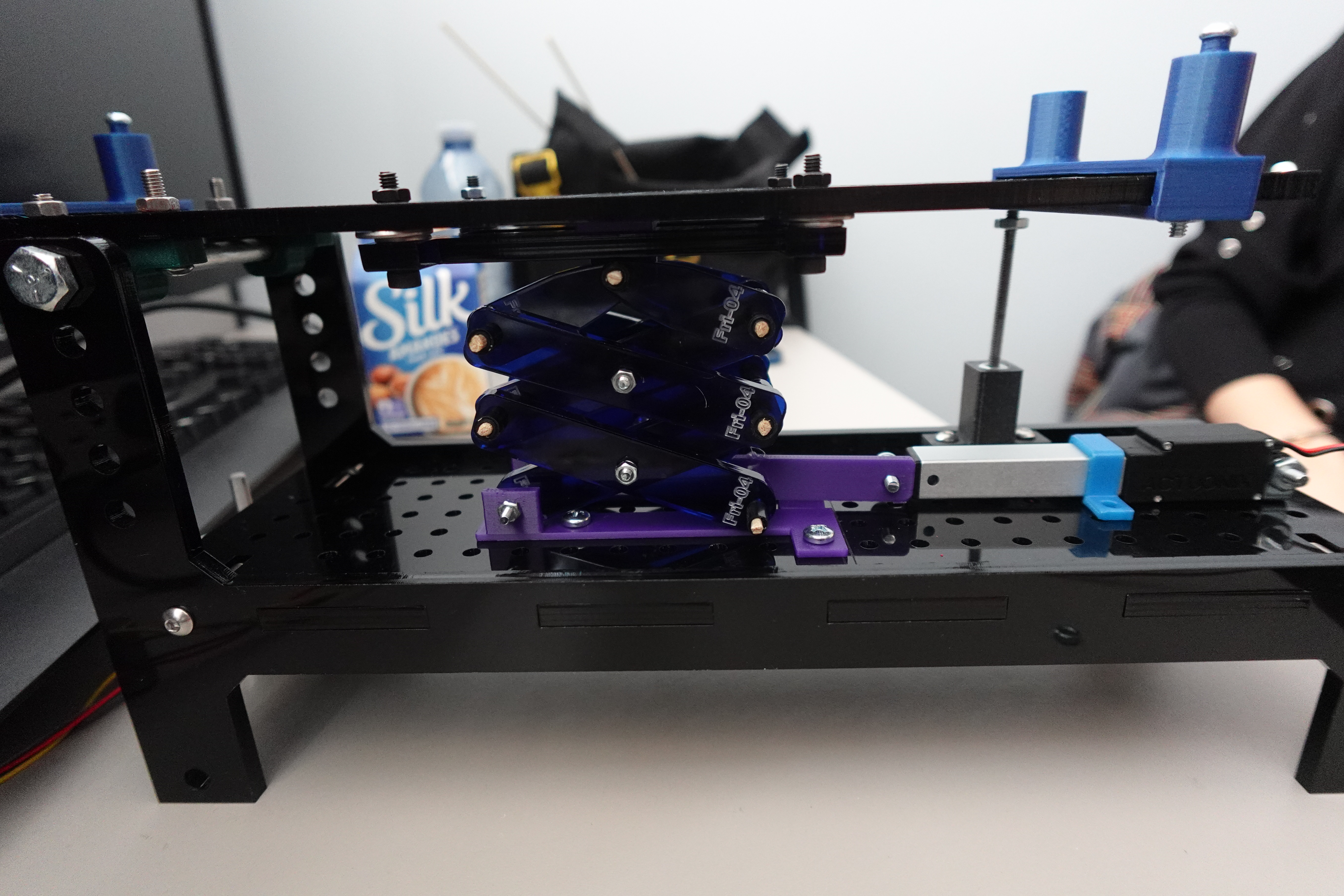

In the end, we settled on the most highly-developed version of the “it’s a stick” concept on the market, a scissor lift.

Next we needed to CAD it. Unless the thing is large enough that it makes sense to have different people working on different parts of it, which this wasn’t, it’s a little bit impractical to have multiple people “make” a CAD model of the same object at the same time; instead, the two of us who wanted to work on the CAD model both made our own versions, and we’d use whichever one ended up working better; and the member who preferred to work on fabrication, and had access to a private 3D printer, worked on that side. Unfortunately, the two of us who wanted to make a CAD model were both so enthusiastic about jumping into it that we failed to notice there were downloadable CAD files representing the already-fabricated parts of the hopper that you could use to make sure your mechanism would actually fit, and we showed up at the next class with two separate models of the mechanism, neither of which actually fit the parts provided. Oops! We fixed that for the next class and both attached our models to the given files. In an unexpected sudden death round of “who’s CAD model works better,” something went oddly and catastrophically wrong with the contraints on my classmate’s model, which had been working just fine, right before we were about to show it to a TA, so mine it was, kicking off a long iteration of files on my computer named things like “preminary CAD”, “final CAD”, “really final CAD”, “Actually final CAD after trying it IRL”, etc, as well as a large array of stray files featuring parts in amusingly unphyiscal situations:

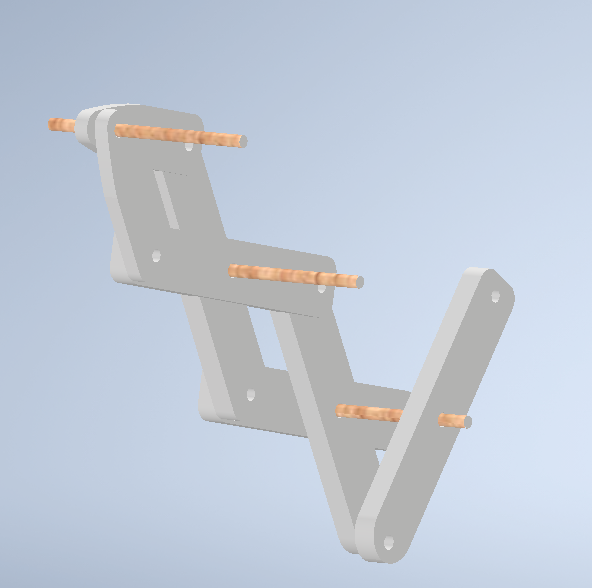

(The one aspect of Project 4 that was unambiguously better than Project 3, for me personally: simply giving files version names… genius.) Anyway, “Actually final CAD after trying it IRL” looked like this:

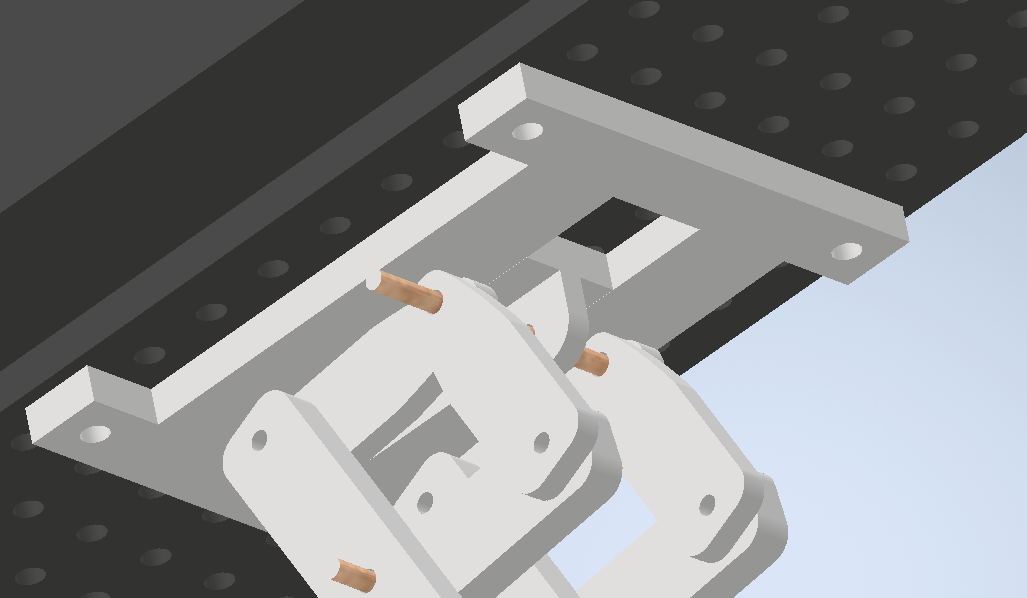

The “after trying it IRL” part refers to changes made somewhat last-minute– the team member with a 3D printer being here essential– where we added a plate by which the slider at the top of the mechanism “hooks in” to the groove it’s sliding along. A previous version, right up until fabrication and testing, worked with the slider that runs along the top of the hopper essentially being held in only by gravity. This worked OK in the CAD assembly:

It actually stayed in pretty well in reality as well, but required a larger amount of force to get “unstuck” from its resting position when the actuator started to move. The fix was fairly simple, and only required re-fabricating one part; we decided to raise the slider rail off of the top with a few washers, and add thin pieces sticking off the slider that would be trapped between the slider rail and the hopper, so all the force of the actuator could only be translated in one direction.

Though there was no reason to think this would work any worse than the previous version, it was a little nerve-wracking in that we didn’t have the opportunity to actually test it on the real-life hopper until our final presentation. However, it fit in perfectly:

And when attached to the moving robot that it had been the computing team’s job to code, successfully put the recycling in the bin, at least the time that we were being marked on it:

As well as lucking out with excellent groupmates on this project, this was a fun experience because it involved a challenge that we wouldn’t necessarily have thought to set ourselves, with obvious standards of success or failure, and we had the fabrication resources to execute our design successfully. In making the CAD model (and re-making it… and re-making it…) I definitely learned some lessons that will (hopefully) make the next time I make something of this nature easier. For instance, an in-retrospect-obvious bit of planning that did not occur to me when I first started the model: why not just decide what size of screws you’re going to use based on what’s easily available at the hardware store, and then make your parts with holes of that size? Instead of doing that, by the end of the project I’d accrued a kind of CAD-cruft whereby the design included three different sides of holes: 4mm for the parts that needed to connect directly to the hopper, 3mm holes requiring screws that I drove all over town looking for, and holes for the dowels that started out 3mm and then had to be changed to match the size of dowel we ended up using.

Also, I learned to absolutely do not under any circumstances make changes to your parts inside your assembly file, even though that is a thing that Autodesk Inventor absolutely allows you to do, because then when you want to actually fabricate the parts, which requires exporting to a 3D-printable format from the individual parts files, you will have a bunch of parts that do not actually have the changes you want to have made to them, and when you ask a TA for help with that situation and explain how you got there, she will only shake her head sadly and say “Oh… dawg…”

We ended up dismantling the mechanism, because that thing had $40 worth of screws on it that I wanted back to be able to re-use, and the teammate who did most of the fabrication wanted to keep the other bits. However, we did each keep a single linkage, which now sits on my bookshelf as a souvenir:

Computing

The second project introduced the use of a virtual invironment built by Quanser. The project involved programming a robotic arm to pick up and put down boxes in various locations; since the actual robotic arms are expensive and delicate, the virtual environment allowed you to make mistakes without fear of damaging the equipment. Here was my final code for the task, which was to randomly spawn six boxes of different colours and sizes and then drop them off at a location that depended on the colour and size.

`ip_address = 'localhost' # Enter your IP Address here

project_identifier = 'P2B' # Enter the project identifier i.e. P2A or P2B

#--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

import sys

sys.path.append('../')

from Common.simulation_project_library import *

hardware = False

QLabs = configure_environment(project_identifier, ip_address, hardware).QLabs

arm = qarm(project_identifier,ip_address,QLabs,hardware)

potentiometer = potentiometer_interface()

#--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

# STUDENT CODE BEGINS

#---------------------------------------------------------------------------------

def pick_up_container(size):

if size == 'small': #if container is small, close the gripper a larger angle

angle = 35 #IF YOU CHANGE THESE ANGLES, ALSO CHANGE THEM IN DROP OFF FUNCTION

else: #if container is large, close the gripper a smaller angle

angle = 30

arm.move_arm(0.6, 0.003, 0.02) #trial pickup location-- could use improvement

time.sleep(2)

arm.control_gripper(angle)

time.sleep(2)

arm.move_arm(0.406, 0.0, 0.483) #this is the home position

time.sleep(5)

def rotate_qarm_base(colour):

positionsuccess = False

old_reading = 0.5

while not positionsuccess:

new_reading = potentiometer.right()

delta = new_reading - old_reading

increment = 348*delta

arm.rotate_base(increment)

time.sleep(0.2)

print(potentiometer.left(),potentiometer.right())

old_reading = new_reading

positionsuccess = arm.check_autoclave(colour)

if positionsuccess:

final_reading = arm.effector_position()

print("Arm is in position")

return final_reading

else:

print("Arm is not in position")

def drop_off_and_return(colour, size, final_reading):

arm.move_arm(final_reading[0], final_reading[1], final_reading[2])

arm.activate_autoclaves()

if size == "large":

arm.open_autoclave(colour)

else:

pass

print("Please move left potentiometer: between 0.5 and 1 for small, all the way to 1 for large.")

potentiometerused = False

while not potentiometerused:

if 0.5 < potentiometer.left() < 1 and size == "small":

potentiometerused = True

arm.rotate_elbow(-15)

arm.rotate_shoulder(35)

time.sleep(1)

arm.control_gripper(-35)

time.sleep(2)

arm.home()

elif potentiometer.left() == 1 and size == "large":

potentiometerused = True

arm.rotate_elbow(15)

arm.rotate_shoulder(30)

time.sleep(0.5)

arm.control_gripper(-30)

time.sleep(2)

arm.home()

arm.open_autoclave(colour, False)

else:

pass

def get_container_info(container):

if container == 3 or container == 6:

colour = 'blue'

elif container == 1 or container == 4:

colour = 'red'

else:

colour = 'green'

if 1 <= container <= 3: #Containers 1, 2 and 3 are small containers

size = "small"

else: #containers 4, 5 and 6 are large containers

size = "large"

return [colour, size]

def main():

import random

usedcontainers = [] #starts at length 0, will be populated with used containers

while len(usedcontainers) < 6:

container = random.randint(1,6) #gets a container with a value in the given range

if container in usedcontainers:

pass #We want to use each container only once

elif container not in usedcontainers:

arm.spawn_cage(container)

usedcontainers.append(container)

containerinfo = get_container_info(container)

colour = containerinfo[0]

size = containerinfo[1]

pick_up_container(size) #picks up the container

final_reading = rotate_qarm_base(colour)

time.sleep(0.5)

drop_off_and_return(colour, size, final_reading)

time.sleep(0.5)

time.sleep(0.5)

else:

print("Random value error!")

if __name__ == "__main__":

main()

#---------------------------------------------------------------------------------

# STUDENT CODE ENDS

#---------------------------------------------------------------------------------`

Modelling

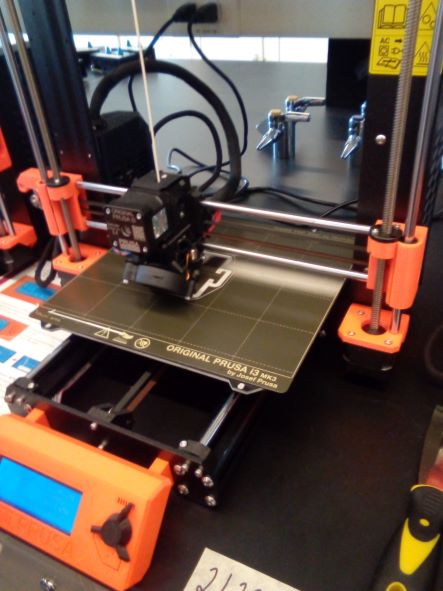

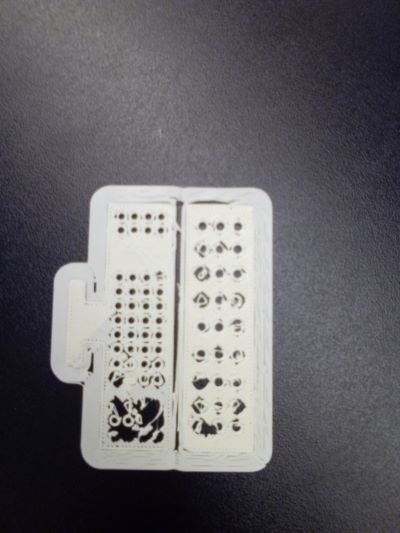

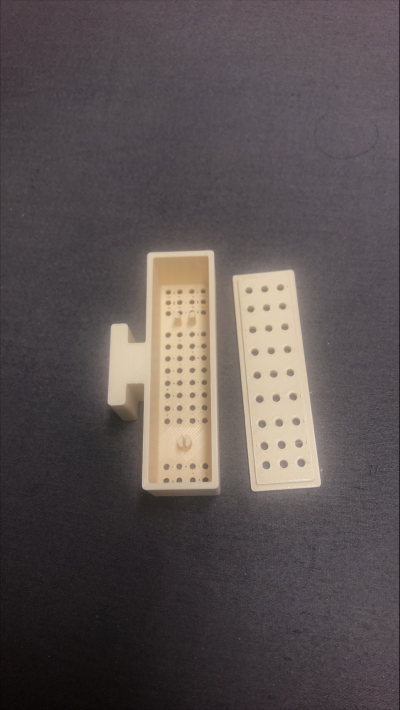

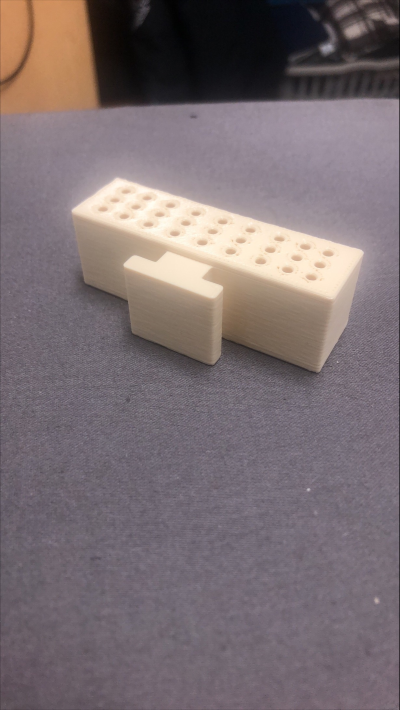

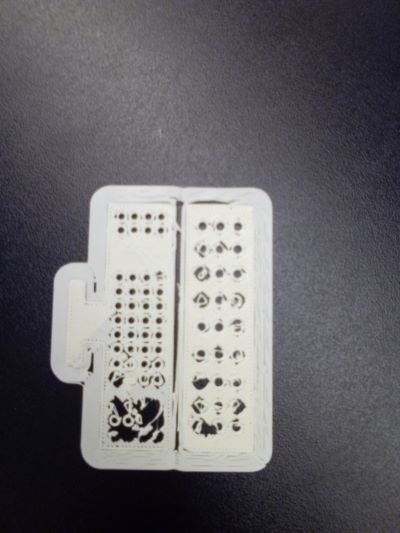

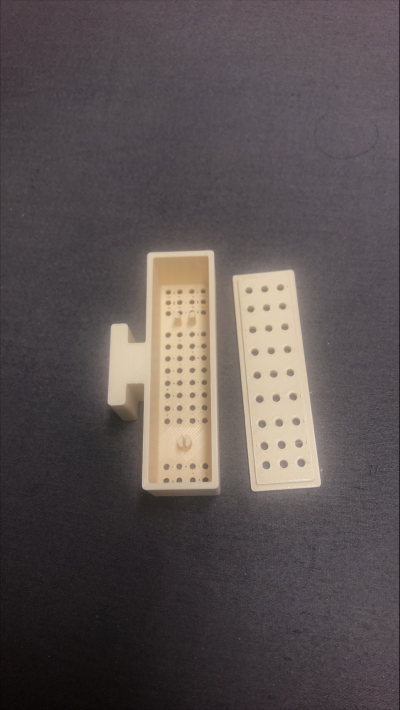

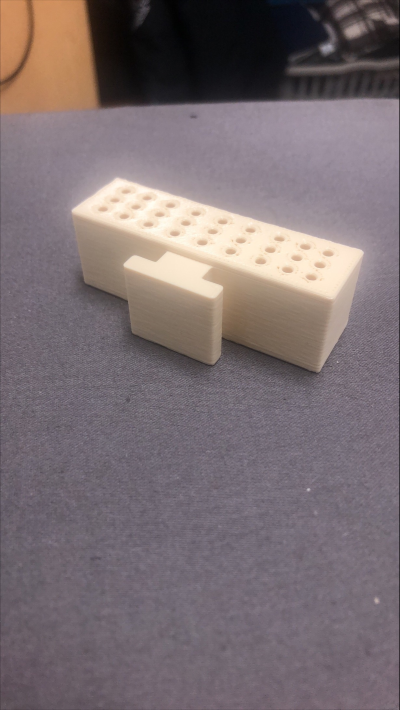

Although I was tasked with writing the code for the concept, there was also a modelling and 3D printing aspect to the project, the idea being to create a box that the robotic arm could pick up and put down. Unfortunately, because of constraints on the availability of 3D printers, print time had to be kept under 2 hours. Since most large 3D print jobs take much longer than that, the box had to be scaled down until it was, shall we say, very cute. However, getting to use the 3D printers did provide an interesting view of how they work. The first print job failed, with the first few layers of the box looking like this:

After a quick consultation with my spouse, who works at the Makerspace at the public library and helps with the 3D printers (and embroidery machine, and laser cutter, etc– did you know the public library could do all that?), it seemed that there wasn’t a fundamental problem with the design (I had thought at first that there were too many holes in the box, and the filament wasn’t able to trace them accurately.) Instead it was just an adhesion problem, and could be fixed by either trying it again or, to be sure, using a glue stick on the printer plate. The next try was successful:

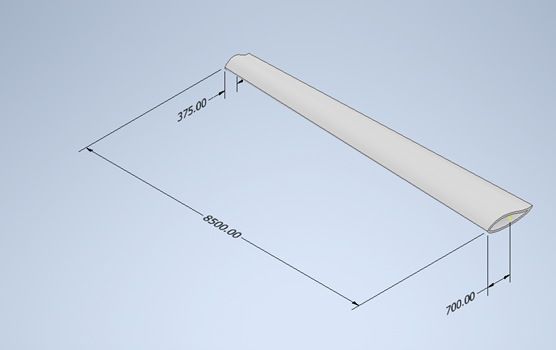

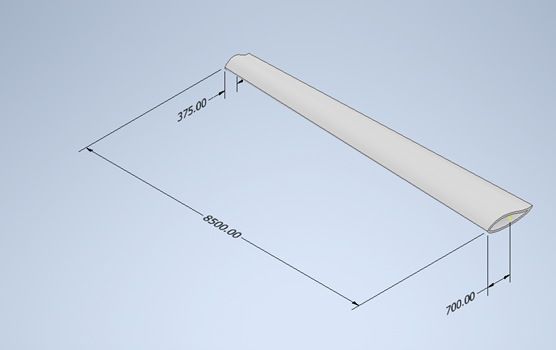

In this project, we were tasked with creating– or rather lightly editing, since much of the design was done for us– a design for a wind turbine blade based on one of four scenarios.

The scenario my group was assigned reads as follows:

You are a part of a group of volunteer engineers in Engineers Without Borders (EWB) that is designing a simple wind turbine for the Guatemalan city of Quetzaltenango. This Guatemalan village is currently off the grid [sic]* and EWB aims to build a wind turbine that can provide enough energy to power simple electrical devices like LED lights. Villagers will assemble multiple units of these simple turbines, which should be long lasting and require little maintenance. Your task is to design a simple wind turbine that is suitable for easy assembly by the villagers with widely available materials. Source: Wired, ‘Engineers Without Borders Bring Tech to Villages Without Power’, 2008. [Online]. Available: https://www.wired.com/2008/03/engineers-without-borders-bring-tech-to-villages-without-power. [Accessed: 24 – July - 2020].

Since the scenario was based on a real-world project, naturally I was curious to find out what happened with it. The Wired article says that “The turbine was created by the Appropriate Technology Design Team of EWB’s San Francisco chapter. Team members like Malcolm Knapp and Heather Fleming spend their nights and weekends inside D2M’s design shop trying to perfect low-tech gadgets for people 2,500 miles away.”

There are also links in the article: one to the Appropriate Technology Design team, a victim to link rot, and one to the San Francisco chapter of EWB’s website. An inspection of that site revealed that the ATDT changed its name to “R&D Group” in 2014. Unfortunately, the link to the “new” R&D group’s website is also dead, and the Guatemala wind turbine project is not listed on that page’s summary of previous ATDT/R&D group projects.

Which is somewhat anticlimactic, in terms of being able to figure out what– if anything– actually happened with the project. However, from the moment I read the original article, I was put in mind of a passage from Tracy Kidder’s Mountains Beyond Mountains, a book that made an enormous impression on me when I first read it, and of which I was reminded by the death of Paul Farmer in February of 2022. In the book, describing Farmer’s early contact with the collaborators and patients who would define his career and the transformative impact of Latin American liberation theology on his work, Kidder writes:

Farmer was learning about the great importance of water to public health, and he was conceiving a great fondness for technology in general, and also scorn for “the Luddite trap.” He liked to illustrate the meaning of that phrase with the story of the time when he came back to Cange from Harvard and found that Père Lafontant had overseen the construction of thirty fine-looking concrete latrines, scattered through the village. “But,” Farmer asked, “are they appropriate technology?” He’d picked up the term in a class at the Harvard School of Public Health. As a rule, it meant that one should use only the simplest technologies required to do a job.

“Do you know what appropriate technology means? It means good things for rich people and shit for the poor,” the priest growled, and refused to speak to Farmer again for a couple of days.

Lafontant was also supervising the construction of a clinic in Cange—the South Carolinians had put up the money. The facility would have a laboratory, of course. Farmer got hold of a pamphlet about how to equip labs in third world places published by the World Health Organization. It made modest recommendations. You could make do with only one sink. If it wasn’t easy to arrange for electricity, you could rely on solar power. A homemade solar-powered microscope would serve for most purposes. He threw the booklet away. The first microscope in Cange was a real one, which he stole from Harvard Medical School. “Redistributive justice,” he’d later say. “We were just helping them not go to hell.”

All throughout this project, the words of Père Lafontant, a Haitian Episcopal priest who died of COVID-19 in 2021, were on my mind. When we were choosing objectives, the student groups who had scenarios taking place in rich countries chose objectives that prioritized “good things for rich people”: a wind farm capable of powering an entire city or country, a roof generator to help people reduce their power bills. Which begs the question: we we, in our design prioritizing low cost and portability, falling into Farmer’s Luddite Trap? And were the original EWB Appropriate Technology Design Team, named after the very concept that Lafontant so colourfully characterized as “shit for the poor,” doing the exact same thing? What kinds of assumptions do we make about the end users of our devices, when we design them to be technology that wouldn’t be sufficient for our own needs? And what would a preferential option for the poor look like in technology design?

*Quetzaltenango is not an off-the-grid village, it is a major city with a distinguished Mayan history. In the article, it is clear that the original intention was for the city to be a manufacturing centre for turbines that would then be transported to outlying villages.

Back in Regina to play Aura Pon’s Romp and Repose.

Our old house for sale… (not by us, the landlord had planned to sell it when we moved out)

That cat in the window of that place on Albert

SCARY SWOLE BUNS I MISSED YOU

This week we played two iterations of a holiday circus show— one in Brandon, and one in Regina. The first show, in Brandon, was in a hockey arena, and featured a Wheel of Death, which I’d never gotten to see live before. Unfortunately, the show in Regina was in the Conexus Arts Centre which is too small for it.

The part for Sleigh Ride featured the signatures of everyone who’d played the show recently– so of course the following evening I got a text from Mike Hope of the Calgary Philharmonic, who was playing the show that evening. (In the Saddledome, so they did have enough room for the wheel…) Sign your rental and touring parts, folks! :D

…yeah, it may not look like much, but… OK, there’s no but to that sentence. If we had the ability to fabricate metal, it could have worked– the idea, not exactly clear from a very quick CAD example, would be to have a fork that used a little spring to move a circular wraparound knife up and down; so you can stick the fork into the food, push the knife down to cut a piece of food around the tines, retract the knife (have it held up there or covered somehow so it’s not pointing at your face?), then use it as a fork. As it is, fork tines aren’t a good candidate for 3D printing because they need to get very thin, laser cutting can only cut flat parts along a single plane, and we would have no way of fabricating a circular knife. So, cutting board it was. A groupmate made a cardboard version of the concept, which a) holds the tip of the knife in place, b) has a slide to push food off the board, and c) has a container on the side for the food to be pushed into.

…yeah, it may not look like much, but… OK, there’s no but to that sentence. If we had the ability to fabricate metal, it could have worked– the idea, not exactly clear from a very quick CAD example, would be to have a fork that used a little spring to move a circular wraparound knife up and down; so you can stick the fork into the food, push the knife down to cut a piece of food around the tines, retract the knife (have it held up there or covered somehow so it’s not pointing at your face?), then use it as a fork. As it is, fork tines aren’t a good candidate for 3D printing because they need to get very thin, laser cutting can only cut flat parts along a single plane, and we would have no way of fabricating a circular knife. So, cutting board it was. A groupmate made a cardboard version of the concept, which a) holds the tip of the knife in place, b) has a slide to push food off the board, and c) has a container on the side for the food to be pushed into.

After this, we spent quite a while trying to figure out how to fabricate a better version with the resources available. The two methods of fabrication available through the class are 3D printing and laser cutting of acrylic. Most of the components we needed were long and flat; theoretically candidates for laser cutting, except that they were longer than the sheet of acrylic that each group was supposedly limited to. (Later we learned that the stated limits were more guidelines than actual rules, but that wasn’t officially circulated information.) Of course there are ways to buy all sorts of these materials, such as a knife– but aren’t we supposed to be, you know, making a thing ourselves? What level of “fabrication” was even expected of us? There was supposed to be a $100 limit on materials, but of course rumours swirled– “I heard that group spent $300 on electronic components and clamed they’d had it all lying around the house,” etc– and direct questions about the expected balance between a professional-looking product and a product we actually fabricated ourselves were met with apparent alarm and confusion.

After this, we spent quite a while trying to figure out how to fabricate a better version with the resources available. The two methods of fabrication available through the class are 3D printing and laser cutting of acrylic. Most of the components we needed were long and flat; theoretically candidates for laser cutting, except that they were longer than the sheet of acrylic that each group was supposedly limited to. (Later we learned that the stated limits were more guidelines than actual rules, but that wasn’t officially circulated information.) Of course there are ways to buy all sorts of these materials, such as a knife– but aren’t we supposed to be, you know, making a thing ourselves? What level of “fabrication” was even expected of us? There was supposed to be a $100 limit on materials, but of course rumours swirled– “I heard that group spent $300 on electronic components and clamed they’d had it all lying around the house,” etc– and direct questions about the expected balance between a professional-looking product and a product we actually fabricated ourselves were met with apparent alarm and confusion.

If it’s not clear– there are straight razor blades sticking out of that cleaver-looking thing. My groupmates found this very funny when I brought it to class the next session.

If it’s not clear– there are straight razor blades sticking out of that cleaver-looking thing. My groupmates found this very funny when I brought it to class the next session.